COVID-19 Social Monitoring Toolkit

Publishing

Making sense of social stories

As reporters scour social media for original UGC that shines a spotlight on narratives about COVID-19 that are pertinent yet untold, they need to be mindful not to transgress ethical boundaries. This also holds true for fact-checkers who might be using UGC or content from another publication to debunk fabricated content. In the section below we offer some insights into how you can avoid ethical and legal issues while republishing content as well as producing debunks in an effective way.

Debunk Best Practices

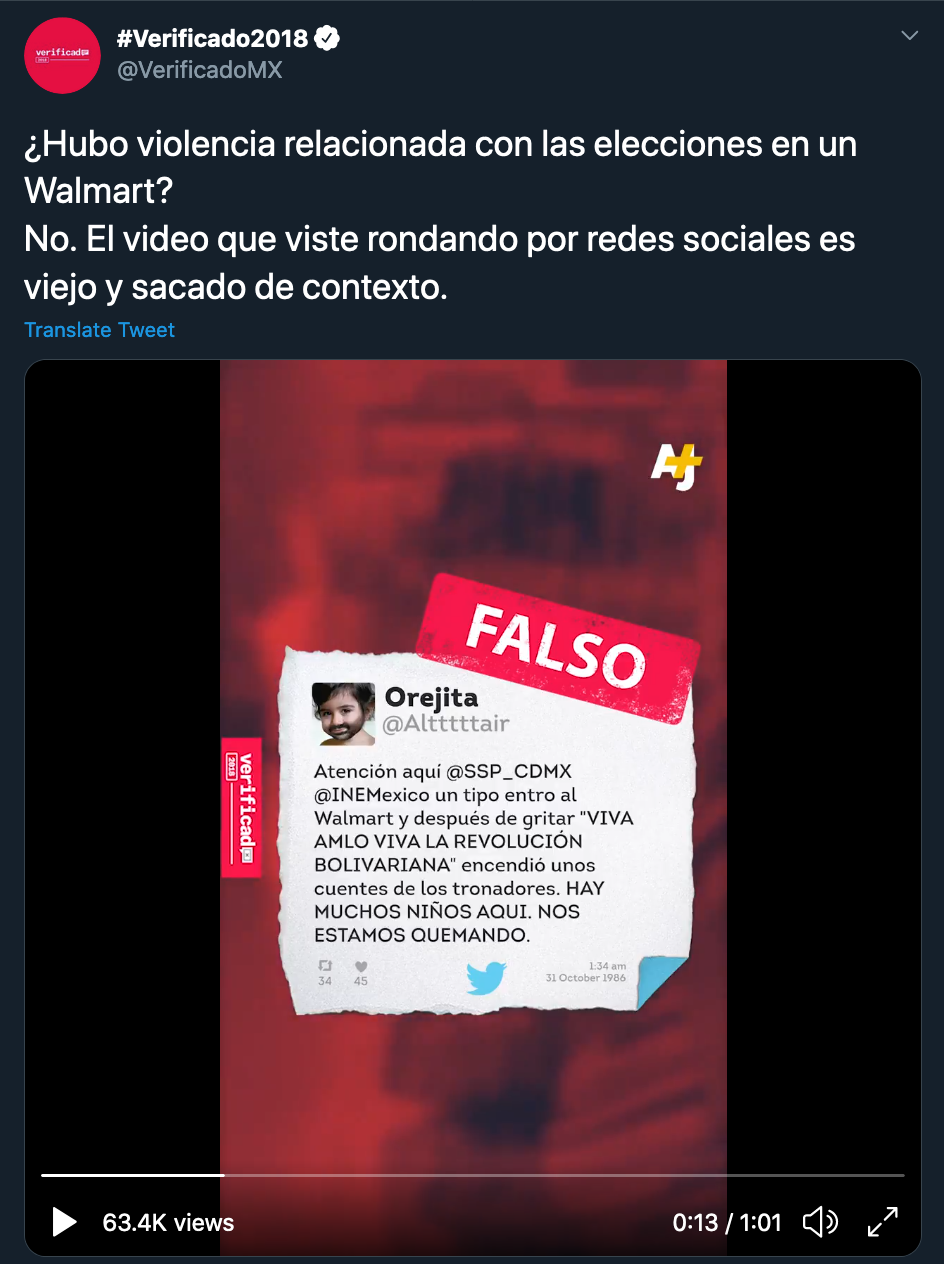

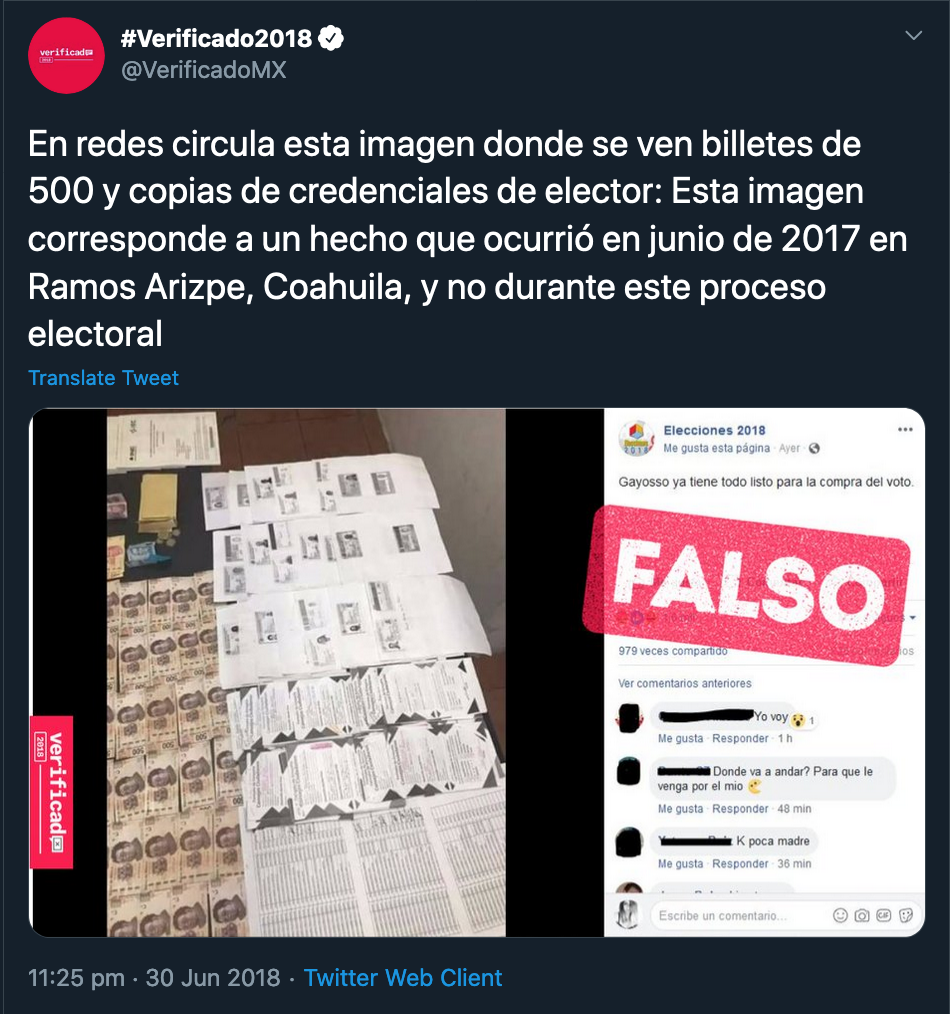

This image is clear and concise — explaining that the viral image is false, and using the text of the tweet to explain the real context.

This clip debunks a viral video. It explains the original context of the video, and why users should be careful before they share content like this — as it's often old.

Aim to produce fact-checked reports that are simple, crisp, yet explanatory and compelling.

Engage audiences more susceptible to misinformation. Example: students, older generation, first-generation Internet users, populations with limited to no access to education.

Remember you cannot change people’s worldview. Try to be creative, use humor wherever possible to adress misinformation.

Create content that is easy to share on social media and closed messaging apps which are popular in your part of the world. Example: short videos debunking misinformation around a particular topic can be powerful, but may have a limited reach in regions where data plans are expensive and the Internet is patchy.

Be transparent in your fact-checking/verification methodology. Share with the audiences the steps and the evidence used in the debunking process. Example: what visual evidence did you discover during your investigation to establish that a widely circulated image on social media, showing people moving about during a lockdown linked to the COVID-19 outbreak, was actually from Pakistan and not India as was being claimed.

A fact-checked report should be able to provide information literacy to the audience that may comprise a large number of people who are not literate.

For a multilingual audience produce reports in multiple languages to ensure a wider reach.Explain the consequences of sharing misinformation through emotions that best appeal to a demographic. Example: at the end of a fact-checked report a standard message can be added to say that sharing misinformation can lead to violence and other forms of real world harm.

Clearing Rights

* Once you have verified the content and validated it as genuine you need to seek permission from the owner(s) to re-use/publish their content.Keep a concise consent form ready after consulting with your legal team to send to the owner(s) of the content.

Such a form should make it absolutely clear what you intend to do with the owner’s content and what permissions they will be granting by agreeing to sign the form.

Be mindful that the owner actually understands the language in which the form is written. Example, a non-English speaker may take “credit” to mean financial compensation as opposed to an acknowledgment in the published piece.

You may need to initiate communication with the content owner over a public platform such as Facebook or Twitter. But make sure to move the conversation to private messaging or email to keep it outside the public domain.

For transparency and efficiency it’s important that the identity of the individual seeking the content be made clear at the outset.

If you are seeking content on behalf of your organisation, use a company account to communicate, this is especially useful if you can leverage the reputation of your brand.

Startups or smaller organisations should include their company’s LinkedIn profile as well as the website link in that initial email so that the recipient has a reference point.

In situations where you need to use your personal email to communicate because you may not have access to your official email, make it clear that you are seeking permission on behalf of your company and not in your personal capacity.

Freelancers seeking content for a story should check with their commissioning editors about the protocol for re-using/publishing user-generated content before reaching out to the content owner.

Do not duplicate outreach. It will confuse the recipient of the message and could delay the process of getting clearance.

Consider the practical effects of reaching out. Are you jeopardising someone’s life by pushing them to share content if they are in hiding or stranded somewhere with their cellphone battery dying? If the answer is yes, then you should look for another source.

Assuming clearance prior to receiving consent could land you into legal trouble.

Every new piece of content will require permission, unless you have been pre-authorised to use follow-up content by an uploader whose content you’ve used previously.

Once you have the clearance, you can use that content by giving due credit to the owner on whichever platform you or your organisation use to distribute content to the public. Example: website, medium page, YouTube channel, or a closed messaging app.